Sidejacked

I Hate Construction.

Specifically when it’s right outside my house and starts at 5:30AM with heavy machinery moving around.

With this said, I’m overdue for a post, and if I don’t set a good example by continuing to blog, why would anyone else? PS. BAS IT’S TIME.

Let’s see what’s on the agenda:

handwaving about C++ draw templatessome obscure vbuf thingshower- make zink usable for gaming

complain about construction- improve shader caching

Looks like the next thing on the list is shader caching.

The Art Of The Cache

If you’re a long-time zink connoisseur, or if you’re just a casual reader of the blog, you know that zink has a shader cache.

But did you know that it doesn’t actually do anything at present?

Indeed, it was to my chagrin that, upon diving back into my slapdash pipeline cache implementation, I discovered that it was doing absolutely nothing. And this was a different nothing than that one time I didn’t actually pass the cache back to the vulkan driver! Yes, this was the nothing of I have a cache, why am I still compiling a hundred pipelines per frame? that the occasional lucky developer runs into every now and again.

But hwhy? Who would do such a thing?

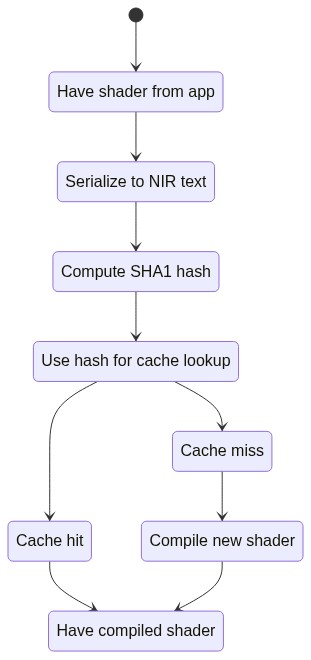

Past recriminations aside, how does a shader/pipeline cache work, anyway? The gist of it in most Mesa drivers is this:

Thus a shader gets cached based on its text representation, enabling matching shaders across programs to use the same cache entry. After noting the success of Steam’s fossilize-based single file cache, I decided to use a single file for zink’s shader cache.

Oops.

The problem in this case was that I was just jamming all the pipelines into a single file, written once at program exit, and expecting the Vulkan driver to figure things out.

But what if the program didn’t exit cleanly? Or what if the write failed for some reason?

In short, the pipeline cache was mostly being written as a big block of garbage data. Not very useful.

Next-Level Caching Technique

Clearly I needed to reeducate myself in the ways of managing a cache, something that, in my former life as a GUI expert, I did routinely, but that I could no longer comprehend now that I only speak bitfields and command buffers.

I sought out the reclusive Timothy Arceri, a well-known sage in many esoteric, arcane arts, and, as I recall it, purveyor of great wisdom such as (paraphrased because the original text has been lost to the ages): We Both Know The GLSL Compiler Code For Uniform Blocks Is Unfathomable, Why Do You Insist On Attempting To Modify It?

The answers I received from my sojourn were swift and concise:

Stop that. Fossilize caching wasn’t meant to work that way.

My thoughts whirling, confidence badly shaken, I stumbled and fell from the summit of the mountain and dashed my heretical cache implementation against the solid foundation of git rebase -i.

What had I been thinking?

It was back to the charts for me, and this time I had a number of different goals:

- go back to multi-file caching (since it’s the only option)

- smaller caches

- more frequent updates

- fully async

Turns out this wasn’t actually as hard as expected?

More Flowcharts (Fulfilling Image Quote For Graphics Blog)

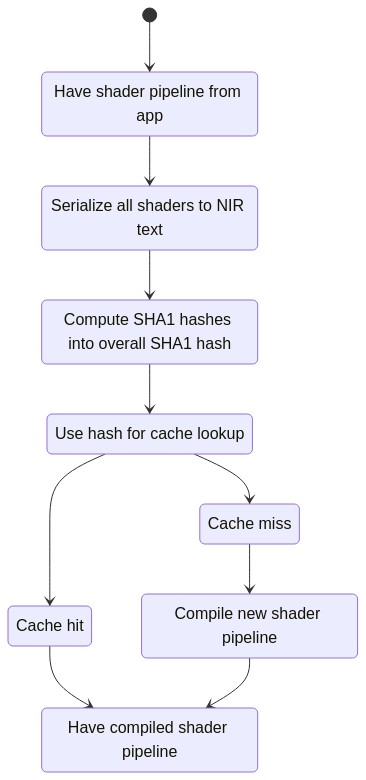

Because we’re all big Vulkan adults, we do big Vulkan pipeline caches instead of wimpy OpenGL shader caches like so:

This has the added benefit of providing all the state variants for a given shader pipeline, saving additional lookups and ensuring that all the potential compiled pipelines are available at once. Furthermore, because there’s a (very) short delay between knowing what shaders are grouped together and needing the actual compiled pipeline, I can dump this all into a thread and handle the lookup while I update descriptors #2021 ASYNC THREADS++++++ BAYBEEEEEE.

But also, also, the one thing to absolutely not ever forget or else it’ll be really embarrassing is to ensure that you add your driver’s sha1 hash to your disk cache lookup, otherwise the whole thing explodes and @tarceri will frown down upon you.